Building a better mouse (er, grasshopper) trap

/Predators can use their own bodies as lures for their prey, but what do they think about modern rock?

Read MorePredators can use their own bodies as lures for their prey, but what do they think about modern rock?

Read MoreWhen biology and philosophy collide, someone is going to get hurt.

Read MoreIn this blog post, we'll explore how the risk of predation affects the cognitive functioning of prey.

Different populations of the same species of prey often face different levels of risk. For example, one population may coexist with a low number or low diversity of predators compared to another population. Experiments and models have revealed that this background level of risk influences how prey respond to future predation risk (e.g., the risk allocation hypothesis). However, it remains to be seen how experience with risk affects prey cognition (e.g., learning new things and remembering old things).

http://www.backwaterreptiles.com/images/frogs/tadpoles-for-sale.jpg

The authors make use of a classic system: tadpoles. These critters have been shown by countless researchers to be sensitive to the risk of predation by changes in body shape, life history, and behavior. Grinding up tadpoles produces alarm cues that inform other tadpoles danger is nearby. Combining these alarm cues with the smells released into the water from a salamander allowed the researchers to use classic Pavlovian conditioning to “teach” the tadpoles about a new risk.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/MonumentIPAVLOV.jpg/170px-MonumentIPAVLOV.jpg

A clever design with a variety of treatments revealed that coming from a high-risk background makes prey less responsive to continued risk (tadpole alarm cues) but more likely to respond to new kind of risk (predaceous salamander cues). Although these effects mostly wore off after ten days, the Pavlovian conditioning only stuck around for tadpoles from a high-risk background.

These results largely confirm hypotheses about how prey should respond to the risk of predation. When living in a scary world (high-risk background), prey cannot afford to freak out at more run of the mill scares. However, these same on-edge prey are better prepared for a new kind of risk than those who have lived a life free of stress (low-risk background). The stress-free prey have the luxury of taking time to evaluate a new risk and see if it is worth responding to, whereas prey living in a scary world take a shortcut and assume the new risk is definitely dangerous. The loss of responses after ten days indicates prey incorporate experience to adjust their assessment of risk: what seems scary at first no longer elicits a response if its scariness is not reinforced somehow. Exactly why prey from a high-risk background would remember a conditioned response longer is not totally clear, but it may be that the conditioning combines with the background to cement the memory more permanently that in the mind of prey from a low-risk background.

http://brokelyn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Risk-Logo-sm-640x774.jpg

So, what does it all mean? Well, prey are clearly not passive players in the predator-prey game of eat or be eaten. Not only can they sense their predators and respond to them, but their history of sensing predator risk colors their response. Information uncertainty is central here, as prey are constantly gathering information and updating estimates of how risky their world is. Perfect information (knowing all risks exactly) isn't attainable, so all organisms must make assumptions about how best to spend their time. Because prey can't respond to predators all the time (they also have to eat, mate, and do other stuff), they are forced to take risks. Computing when and where to take these risks is complicated, and the prey we see alive today are the offspring of parents who did a good enough job solving these problems. If the ability to do these risk-taking calculations is heritable, then we would expect prey to continue to improve their ability to avoid predators. However, predators evolve as well, keeping life interesting for both prey and scientists who study predator-prey interactions.

This is the first of my blog posts wherein I'll share my thoughts on scientific papers I read. The only unifying theme will be stuff that catches my eye, though I am typically drawn to behavior and ecology, often focusing on predator-prey interactions. Spiders may also feature prominently. Anyway, on to the paper!

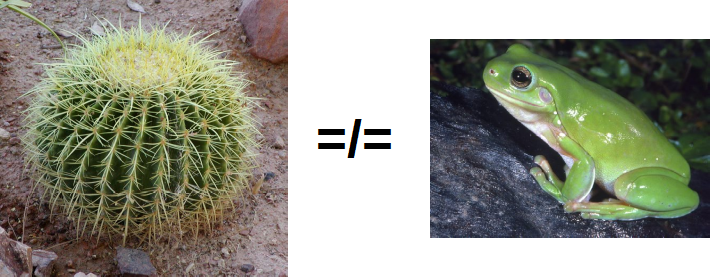

The authors review similarities and differences in how plants and animals respond to the risk of being eaten. Spoiler alert:

(https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0d/Echinocactus_grusonii_1.jpg)

(http://australianmuseum.net.au/uploads/images/11950/frog%20caerulea_big.jpg)

All living things face similar challenges in the ultimate goal of passing genetic material through offspring into the future. Most (all?) organisms must avoid being eaten, whether by herbivores (enemies of plants) or predators (enemies of animals). Although these terms are somewhat murky (re: seed predators), it is clear that sensing and responding to the risk of being consumed would be beneficial.

Plants are different from animals in many ways, and two of the most obvious ones (movement and structure) are rather important when considering how individuals deal with the risk of being eaten.

Movement: Being rooted to the ground limits mobility, so plants often respond to herbivores by changing growth patterns or moving substances (e.g., poisons) from one place to another. Animals, on the other hand, can usually get up and run away from danger, though while doing so they lose out on time spent doing other stuff (e.g., eating). A less obvious effect of the movement differences between plants and animals is the ability to acquire information about the risk of being consumed. Plants are fairly limited in the distance over which they can sense risk, whereas animals can sometimes sense a predator long before it is in danger.

Morphology: Compared to most animals, plants have relatively un-specialized organs with a high level of redundancy. Compare the breathing apparatus of a fern to that of a tern. Ferns breathe through their leaves, of which they have many. Terns breathe through their lungs, of which they have only one pair. Therefore, plants are more tolerant of partial consumption than animals, which feeds back into the fact that their responses to herbivores are slower than the responses of animals to predators. This tolerance of partial consumption allows plants to respond to very reliable cues (“I'm actively being eaten!”), whereas animals often rely on indirect cues (“Smells like a predator has been here recently”).

(http://s3-production.bobvila.com/articles/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/fern-gardening.jpg)

(http://static.comicvine.com/uploads/original/0/2317/965346-tern.jpg)

I was surprised to learn that plants can defend themselves after sensing some indirect cues: herbivore eggs and herbivore mating chemicals (pheromones). The eggs will soon hatch into tiny lawnmowers of doom, built to demolish the plant on which they live. Chemical cues of mating herbivores are a precursor to eggs, so plants that “know” herbivores are mating nearby is enough to trigger defenses in preparation for being consumed. Pretty cool stuff!

Figure one from the paper lays out basic similarities and differences between plants and animals. Dogs clearly don't tolerate leg amputation well...

An interesting comparison can be drawn between plants and plant-like animals, such as corals. Animals that don't move share many limitations with plants, and they have evolved similar ways of managing the risk of being consumed. We always look for examples like this in biology, as they serve as strong tests of our hypotheses. If corals and plants did not share similar responses to the risk of being eaten, then arguments based on lifestyle (e.g., mobility and morphology) would not be as compelling.

(http://www.lowes.com/projects/images/how-tos/Lawn-Landscaping/choose-the-right-grass-for-your-lawn-hero.jpg)

(http://images.nationalgeographic.com/wpf/media-live/photos/000/013/cache/coral-polyps-henry_1387_990x742.jpg)

Overall, a sharing of ideas between plant and animal researchers will likely lead to new, productive research programs. An odd, but very interesting, collection of articles in Behavioral Ecology from 2013 contains an interesting discussion between plant and animal biologists about if and how plants may communicate with each other through sound. Continued cross pollination between researchers in these historically separate fields is rather exciting and should be fruitful (see what I did there?).

Powered by Squarespace.